Where is homeland? - Part 1

This is the first entry in a series of reflections on belonging, memory, and the meaning of homeland

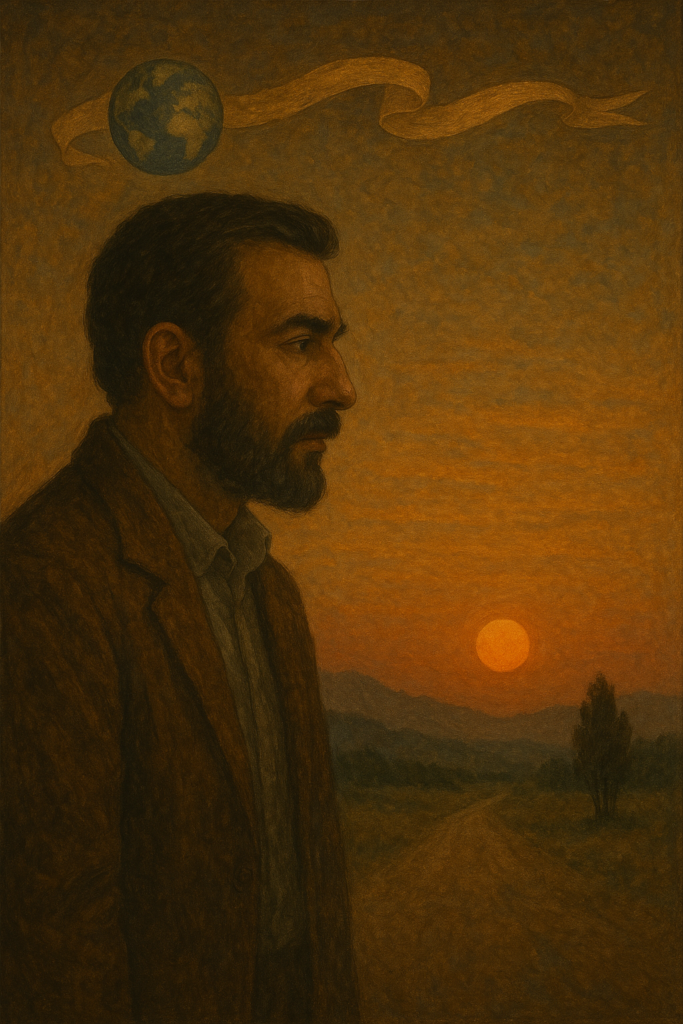

When I was younger, the word homeland carried little meaning for me. This was not because there was anything wrong with the home I had, but because I resisted the very idea of belonging. In the utopian, carefree world of my early twenties—after having travelled alone and lived in different countries—I imagined myself a citizen of the world, or even something larger: a man of the universe. In those years, I thought I had achieved my own ideal justice simply by refusing to be defined by borders.

The idea of cosmopolitan citizenship was not unique to my youthful imagination. Diogenes of Sinope declared himself a “citizen of the world” in the 4th century B.C. He was the ultimate cynic, the sort of man who, when Alexander the Great offered him anything he wished, replied: “You are blocking my sun. Step aside.” To my mind, there was strength in Diogenes’ rebellion, and rejecting the notion of home felt like the first step toward liberation.

The Persian poet Saʿdī, in the opening to one of his most famous poems, advises: “Bind your mind to neither a single companion nor any one land, for lands are many and companions come in plenty.” Saʿdī was not a Sufi, but many Sufis would have embraced that counsel. Ibn ʿArabī, who lived in the same age as Saʿdī, certainly considered himself unbound by any place. For these men of spiritual adventure, home could flow like the wind; wherever the wind turned, they could reside.

For years, I identified with such sentiments. Yet when I completed my Ph.D., another desire took hold of me—a desire to return home. I remember the exact moment it emerged. On the night of my Ph.D. examination, I took a long walk through the old streets of Nottingham. It was just me and the fading shouts of the usual drunks spilling out of the pubs. As I walked up the high alleys of the city, a voice grew louder inside me: Go back. Go back home.

Perhaps I took that inner voice too seriously, but I could not ignore the yearning that followed. I, the self-professed citizen of the world, suddenly found myself at the mercy of a longing I had never anticipated. Instantly, images flooded me—the smile of my mother, the noisy streets of Iran, the bright alleys of Isfahan, the whirring of old motorbikes, the herbal scent drifting from traditional medicine shops, the elderly men singing as they cycled through the bazaars. All at once, it felt like time—time to return, if not to “home,” then to the place I knew better than anywhere else.

I thought I could go back and still remain unattached—that simply being based somewhere did not mean I belonged there. But the desire to return marked the beginning of a shift I had long resisted. Perhaps it was a self-rationalization, one of those stories we tell ourselves to cover a blind spot we already sense but refuse to acknowledge.

Psychologists have long described the vulnerability behind such longings. Freud put it starkly when he framed this impulse as a “return to the womb”—a retreat to oneness, to a center, to safety. And I needed safety. In my youthful ignorance, I was too proud to admit it.

I remember the flight back home with unusual clarity. The hours moved slowly, each minute feeding the rising excitement and anticipation of all the things I believed I would do—the differences I imagined my presence could make. An image from Kim Ki-duk’s Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring kept resurfacing in my mind: a man wounded by the excesses of his own desire returning to the place he once fled, seeking to untie the rope he had cruelly fastened to a creature’s legs years earlier.

For me, that scene became a metaphor for my own return. I told myself that I was going back not only for safety, but to loosen the knots of past mistakes and perhaps illuminate a path forward. In that framing, return was not attachment but liberation—a reclaiming rather than a retreat. This was the story I held onto, the narrative that consoled me as the plane cut through the night sky and carried me back to the place I had once insisted I did not need.

Upon my return, I was given something close to a hero’s welcome by my family and by many of my high-school friends who had heard the news. After the years of seclusion that had defined my Ph.D. research, the warmth felt at once overwhelming and strangely unsettling. Yet it also carried the promise of a beginning—a beginning toward a future whose contours I could not yet see.

In the rush of exchanged greetings, Sina—the oldest friend of my childhood—insisted on driving me home. My mother, despite her hesitation, agreed. The familiar smell of old cigarettes in the car stirred not disdain but recognition. After all, this was the friend with whom I used to sneak down to the banks of the Zayandeh River, hiding in the shadows to steal a few forbidden puffs.

Old habits die hard. He did as was his custom: struck a match, its brief flare lighting his bearded face. He smiled and said, “Cigarettes without matches are like nights without stories.”

As the car started its soft, woozing hum, I eased into the strange comfort of arrival. Then the CD player clicked, and an old song filled the car:

Vuelvo al sur

Como se vuelve siempre al amor

Vuelvo a vos

Con mi deseo, con mi temor